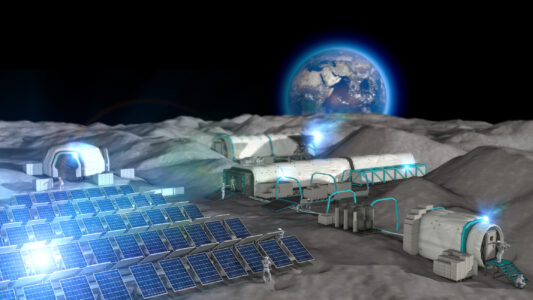

The search for extraterrestrial life is one that intrigues and inspires. Are we truly alone in the universe? Although the definition of extraterrestrial life is as vastly different as the planetary bodies which they may inhabit, the possibilities that could arise upon the discovery of life outside Earth are unlimited. If life can be sustained elsewhere, what new doors could this open? Could humanity branch out beyond our own backyard and even further than our planetary neighbor, Mars?

These questions and more are often the basis for launching spacecraft to various planets and moons in the solar system. These spacecrafts often engage in missions designed to search for microbes. Additional tools such as large radio telescopes are designed to listen for signals emitted throughout the galaxy, and scientists now aim to probe planets orbiting other stars for signs of life or the ability to sustain life.

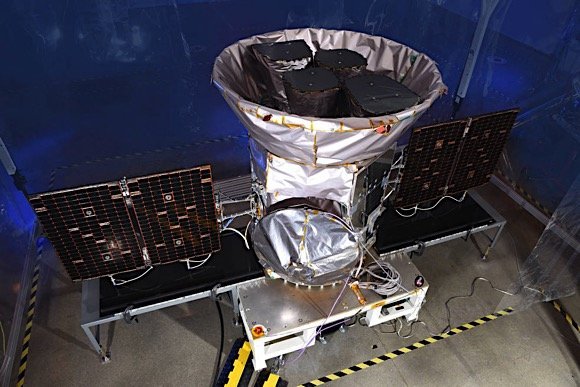

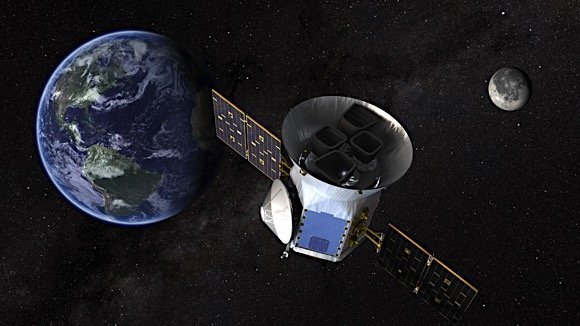

NASA is set to launch its Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) on Monday, April 16thon a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. TESS is a NASA Astrophysics Explorer mission. Led and operated by MIT, TESS is designed to scan and measure the brightness of stars within approximately 300 lightyears. It will observe these stars and any dimming that occurs as planets orbit. The mission is projected to increase the list of known exoplanets by upwards of 400 per cent.

Over 2,500 exoplanets were discovered via a similar method employed by the Kepler space telescope, and an additional 2,500-plus are awaiting confirmation. Of these, around 30 are rocky planets approximately the size of Earth and within the Goldilocks Zone, the distance at which liquid water can exist and sustainable life is possible. Kepler is reaching the end of its life cycle as it will soon run out of fuel following a mission lasting nearly a decade. Anticipating the end of this current mission, NASA set out to create and prepare Kepler’s replacement, TESS.

“TESS is really a finder scope,” says George Ricker, principal investigator of the TESS mission and director of MIT’s CCD Imaging Laboratory. “The main thing that we’re going to be able to do is find a large sample from which the follow-up observations can be carried out in decades, even centuries to come.”

Natalia Guerrero, deputy manager of TESS Objects of Interest, likened TESS to a scout. “We’re on this scenic tour of the whole sky; and in some ways, we have no idea what we will see,” she said. “It’s like we’re making a treasure map. Here are all these cool things. Now, go after them.”

The area which TESS will observe is roughly 350 times larger than that of Kepler. However, TESS will have less time to collect light in each part of the sky. For this reason, it will need to focus on stars which are closer and brighter. Ricker and his colleagues have comprised a list of 200,000 particularly bright stars which they would like to more closely observe. The satellite will create pixelated images of each star. The images will be taken every two minutes in order to capture the moment that a planet crosses its path. Full-frame images will also be taken every 30 minutes, capturing the stars in a specified strip of the sky.

“With the two-minute pictures, you can get a movie-like image of what the starlight is doing as the planet is crossing in front of its host star,” said Guerrero. “For the 30-minute images, people are excited about maybe seeing supernovae, asteroids, or counterparts to gravitational waves. We have no idea what we’re going to see at that timescale.”

Creating a larger map of nearby exoplanets will allow for vastly increased discoveries, as well as closer and more detailed observation.

“The TESS survey should be comprehensive enough that we should be well positioned to essentially find all of these candidates and certainly the ones that are most promising,” said Ricker.

Sara Seager, deputy director of science for TESS, will scour the images for dips in starlight which indicate that a planet may have passed in front of its star. Seager and her team will also use cues from the imagery to determine the mass of a potential planet.

“Mass is a defining planetary characteristic,” said Seager. “If you just know that a planet is twice the size of Earth, it could be a lot of things: a rocky world with a thin atmosphere or what we call a “mini-Neptune,” a rocky world with a giant gas envelope, where it would be a huge greenhouse blanket and there would be no life on the surface. So, mass and size together give us an average planet density, which tells us a huge amount about what the planet is.”

Seager also believes that continued observation may yield surprising results, including the existence of life. “There’s no science that will tell us life is out there right now, except that small, rocky planets appear to be incredibly common,” she said. “They appear to be everywhere we look, so it’s got to be there somewhere.”