As the global energy crisis continues to drive worldwide shifts to renewable power, wind, and solar energy are at the forefront of everyone’s minds. Gone are the days when these two clean, green sources of power cost too much to be considered viable options; the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2023 report predicts that renewables are set to account for over 90% of global electricity expansion over the next five years, dethroning coal to become the world’s largest source of electricity by early 2025. In this forecast period, global wind capacity nearly doubles, one-fifth of which is accounted for by offshore wind projects. [1]

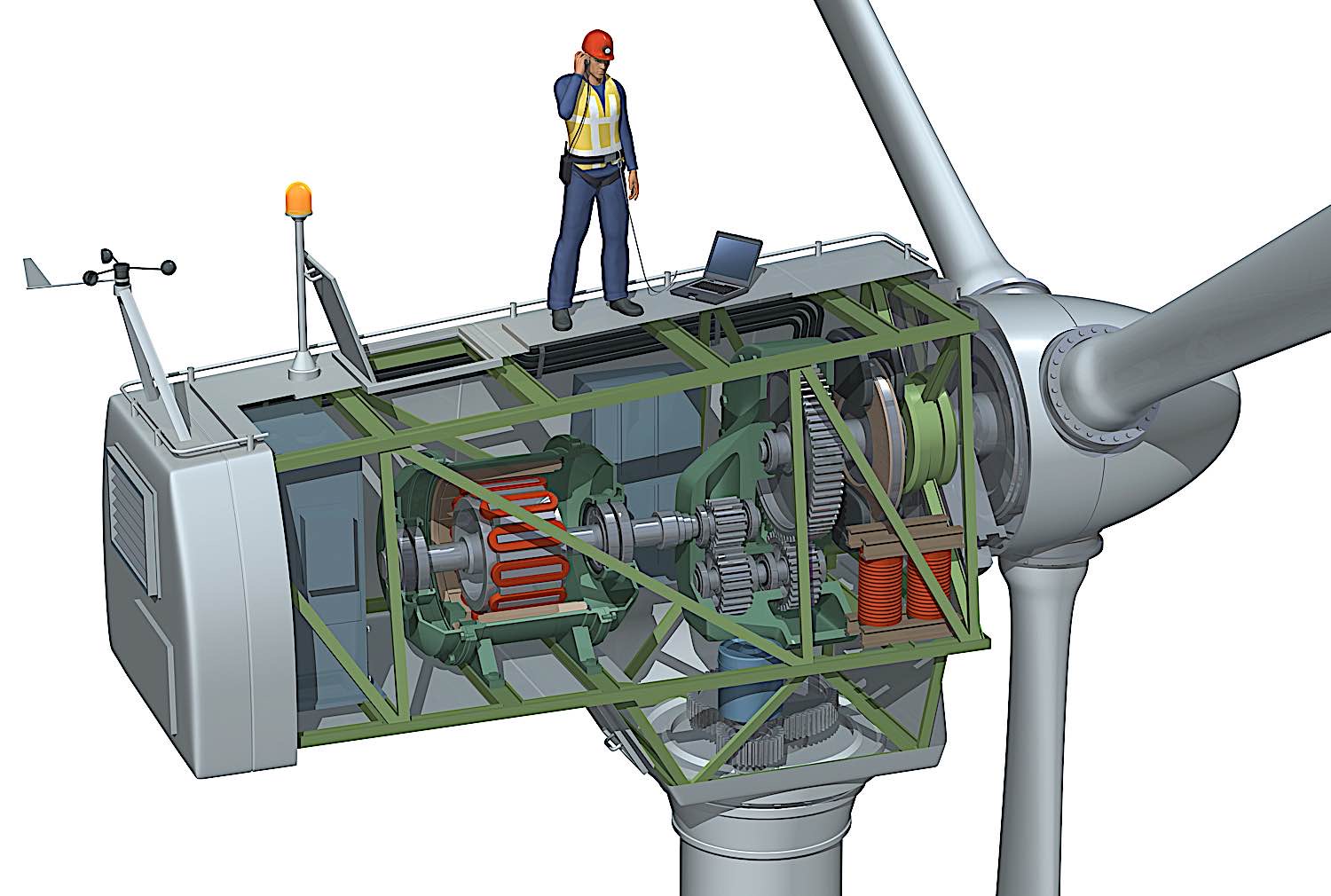

Unlike the photovoltaic cells of solar-powered plants, wind turbines are a visually striking symbol of green energy; they’re iconic and instantly recognizable, towering above people with their looming height and blades.

Innovation in the wind power industry hasn’t stopped, however, and while wind turbines are effective, they aren’t the only option.

Wind power is becoming big – perhaps too big

Major sector players have developed massive new turbines, leading many to believe that the era of super-sized on and offshore structures was just around the corner. For example, last year in America, the construction of a 900-megawatt project called the Vineyard Wind 1 had begun. Described as “the nation’s first commercial-scale offshore wind farm”, the facility will use 13 MW versions of GE Renewable Energy’s Haliade-X turbines, and have a height of up to 260 meters, 107-meter blades, and a rotor diameter of 220 meters. [2]

GE isn’t the only company dreaming big either. August 2021 saw China’s MingYang Smart Energy releasing details of a design that would be 264 meters tall and have 118-meter blades.

The Danish firm Vestas was working on a 15-megawatt turbine that would have a rotor diameter of 236 meters and 115.5-meter blades.

Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy was developing a turbine that would feature a rotor diameter of 222 meters and 108-meter blades. [3]

It’s clear that these size increases were motivated by something more than ego – the U.S. Department of Energy notes that turbine towers are “becoming taller to capture more energy, since winds generally increase as altitudes increase.”

They also explained that bigger rotor diameters “allow wind turbines to sweep more area, capture more wind, and produce more electricity.”

Longer blades “capture more of the available wind than shorter blades – even in areas with relatively less wind.” [4]

Issues with bigger wind turbines

Surely the availability of huge turbines on the market is a good thing. Yet, their sheer scale poses problems for the sector, such as installation costs and logistics, as well as demand and supply imbalances.

Research from Rystad Energy shows that demand for vessels that are able to install larger offshore turbines will outgrow supply by 2024. They stated that operators “will have to invest in new vessels or upgrade existing ones to install the super-sized turbines that are expected to become the norm by the end of the decade, or the pace of offshore wind installations could slow down.” [5]

Martin Lysne, senior analyst for rigs and vessels at Rystad Energy, said in a statement that, “when turbines were smaller, installation could be handled by the first-generation fleet of offshore wind vessels or converted jackups from the oil and gas industry,” also going on to note that since operators were continuing to favor larger turbines, a “new generation of purpose-built vessels” would be needed to meet demand.

Those specialized vehicles are neither cheap nor easy to make. As an example, U.S. firm Dominion Energy is heading a consortium that is responsible for building 472-foot Charybdis, vessels that will cost an estimated $500 million which are able to install current turbines as well as next-gen ones of 12 MW or more. [6]

There are also many concerns over wind turbines and ecosystem damage. It’s no secret that wind turbines have a particular effect on birds.

The U.K.-based Royal Society for the Protection of Birds states that although wind power “is one of the most advanced renewable technologies” wind farms still mustn’t “harm birds through disturbance, displacement, acting as barriers, habitat loss and collision”, and that “impacts can arise from a single development and cumulatively multiple projects.” [7]

These issues are among those that have led the wind power industry to seek alternatives for obtaining wind power.

Wind Catching Systems

Wind Catching Systems was established in 2017 with headquarters near Oslo, Norway. They are focused on developing what they call “a floating wind power plant based on a multi-turbine design”. [8]

The system, known as the Windcatcher, is focused on maximizing “power generation from a concentrated area”. Turbine installation and maintenance uses an elevator-based system that’s incorporated into its design.

The Windcatcher doesn’t exist physically just yet, but on paper it looks like an expansive, water-based wall of rotating blades. CEO Ole Heggheim says that their “large model” would measure in at around 300 meters tall and 350 meters wide. Its realization won’t happen in the near future, however. The large version of the Windcatcher would use 126 1-MW turbines, but a planned pilot model will have between 7-12, Heggheim said, with the exact number to be confirmed in the next few months.

The CEO added that after the pilot, Wind Catching Systems will “most likely build an intermediate size, probably around 40 megawatts, before we go for the large size.”

Offshore wind generation doesn’t always have to have bottoms that are fixed to the seabed. Floating turbines exist as well and have the advantage of the ability to be installed in far deeper waters. In recent years, major economic players such as the United States have made their interest to increase floating wind installations known. [9]

Demonstration projects that amount to around 125 MW-worth of floating wind power have been installed globally, with another 125 MW under construction. That pipeline is growing quickly. There are over 60 gigawatts of offshore wind projects across the world in planning stages; in terms of planned capacity, some of the top countries are South Korea, the UK, Brazil, and Australia. [10]

As companies and countries around the world do their best to solve the energy crisis, cut their emissions, and hit net-zero goals, firms such as Wind Catching Systems are starting to attract more and more notable backers. [11]

The company stated in June 2022 that it had entered into a strategic agreement with General Motors and secured investment from GM Ventures. That agreement was related to “collaboration covering technology development, project execution, offshore wind policy, and the advancement of sustainable technology applications.” [12]

In February this year, Enova, which is owned by Norway’s Ministry of Climate and Environment, awarded Wind Catching Systems a pre-project grant of 9.3 million Norwegian Krone, or about $872,500. The company said that the grant would “support the initial implementation of a full-scale Windcatcher,” and that “through the pre-project, Wind Catching Systems will mature and validate the technology and cost estimates for a full-scale Windcatcher.” [13]

Other novel ideas for wind power generation

The Windcatcher is an interesting, new way to harness the power of the wind. It’s but one of a range of ideas that have cropped up in recent years.

There are others, such as Vortex Bladeless’ system, featuring a cylindrical mast and no blades, SeaTwirl’s vertical-axis floating turbine, and Kitemill’s kite-like system which is tethered to the ground.

These “disruptor” designs may very well be the future of wind power, but they are faced with a long road ahead if they are to really challenge current on and offshore turbines. Although nowhere near as old or established as the fossil fuel industry, the wind power industry has firm roots entrenched. There are established methods, regulations, ideas, and methods. Disrupting it is a gargantuan task which requires significant interest, investment, time, and patience.

Yet, it’s clear that there are many out there who are working on it. The outcome remains to be seen, but it’ll be exciting if they succeed.

Sources

[1]

IEA – Renewable power’s growth is being turbocharged as countries seek to strengthen energy security

[2] [3] [4] [5] [6]

CNBC – The race to roll out super-sized wind turbines

[7] [8] [9] [11] [12] [13]

[10]

MIT Technology Review – The wild new technology coming to offshore wind power