Canadians do a good job of creating new businesses, but we don’t do so well at growing them. With help from governments, educational institutions and others, Canada’s entrepreneurs have been successful at starting businesses, but they haven’t led to the expected economic benefits, according to a study by the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC).

Its new report, Breaking Barriers: Ontario’s Scale Up Challenge, says that businesses in the province face a number of barriers that prevent them from scaling up to become the next generation of large and globally competitive Canadian firms. While American firms are more likely to experience rapid growth after start up, Canadian equivalents are more likely to experience little growth or even rapid decline.

The emergence of new corporate giants based in Canada “has not matierialized,” the report says. The objective of the report was to determine why.

The perplexing reality is that while Canada, as well as Ontario, is a leader in early stage entrepreneurial activity, the country is not producing the high-growth firms in knowledge-intensive sectors that everyone agrees are necessary to compete globally. The country’s failure to scale up its companies is a “critical gap” in its business growth strategy, one that is costing the economy.

To illustrate the point, the OCC report states that while large companies, defined as those with more than 500 employees, account for less than 1 per cent of all businesses in Canada, they produce nearly half (46 per cent) of the country’s GDP. Large firms obviously employ more people, but employees of large firms also tend to be more productive, the report says. Large firms are able to take advantage of economies of scale, and there is an increased likelihood that they are exporting products.

High-growth businesses made up just 18 per cent of Canada’s growing companies in the years 2000–2009, but created 47 per cent of new jobs.

An important result of encouraging more firms to scale up is potentially increasing the number of firms that reach a larger size. This is because large firms tend to contribute a disproportionately greater amount to overall economic activity. In Canada, large companies (companies that employ 500 or more people) account for less than one percent of all businesses, but produce nearly 46 percent of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While large firms do employ a significant proportion of Canadian workers (36 percent), employees at these firms are also more productive.

Barriers preventing scaling up

First, there is a shortage of know-how. About one in four respondents to an OCC survey reported that access to talent was a barrier to their growth. Firms reported an inability to find management talent with experience in implementing go-to-market strategies. Other research has found that the Canadian management talent pool lacks expertise in sales, marketing and organizational design.

Access to capital or financing is cited as another barrier, though the OCC report notes that it is not clear how significant this challenge actually is.

More important is a lack of government support and incentives that align with scaling up objectives. While there are more than 120 government programs in Ontario to support business growth, they may be failing because they don’t actually influence growth. Scaling up has not been a “key priority” in Ontario, the report finds.

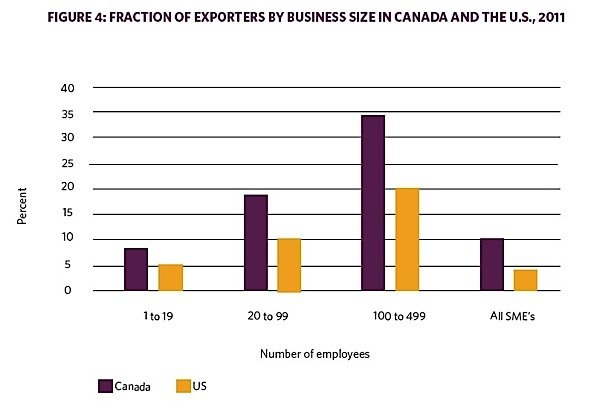

Perhaps most critically of all, too few Canadian firms—under 12 per cent—are exporting their products (15 per cent in Ontario). This in spite of the fact that the benefits of international trade are clear. Exporters, the report says, “disproportionately contribute to the Canadian economy.”

To remedy these problems, the OCC recommends a number of steps, including the following.

- Access to talent could be improved by creating a “scale up visa” that would give companies accelerated access to international candidates and make the process of hiring them less cumbersome.

- Access to business financing should be improved by first gaining a better understanding of existing gaps, which are not clearly understood.

- Public programs and incentives should be better aligned to encourage businesses to scale up by focusing on high-growth firms and those with high-growth potential, and by delaying taxation on corporate income growth. Ontario’s current tax system contains few incentives to encourage firm growth.

- Greater international trade should be encouraged by greater government investment to support exports. Business support programs should be linked to exporting.