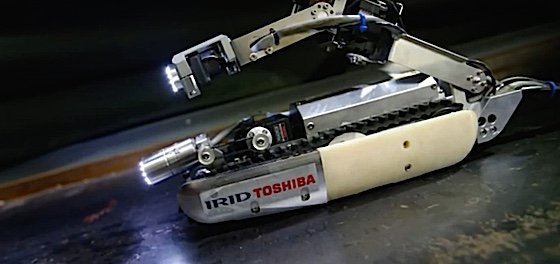

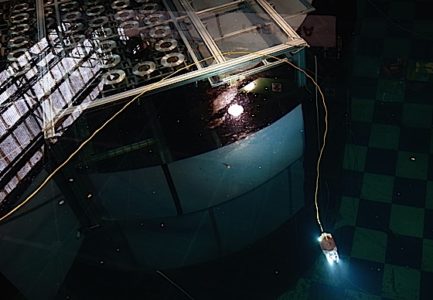

Toshiba, a Japanese industrial group unveiled a swimming robot designed to probe damage from meltdowns that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi.

Extreme levels of radiation and significant structural damage made it difficult to probe damage to the reactors, and the agency hopes that the robot will be able to change that. It will send the probe into the primary containment vessel this summer to study the extent of damage, as well as locate some of the melted fuel.

The robot maneuvers with tail propellers and collects data using two cameras and a dosimeter. The plan is to locate and start removing the fuel after Tokyo’s 2020 Olympics.

The robot was developed by the Toshiba Corp. and the government’s International Research Institute for Nuclear Decommissioning. Former US Nuclear Regulatory Commission Chief, Dale Klein, revealed that it could take six months to a year to obtain necessary data and decide on how to remove the fuel. He stated that scientists “will have to identify where it is. Then they will have to develop the capability to remove it.

No one in the world has ever had to remove material like this before. So this is something new, and it would have to be done carefully and accurately.” The developers and its partners have also designed some basic robots, including a muscle arm robot made by Hitachi-GE Nuclear Energy and another arm robot created by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, in order to approach the debris from the side of the reactors. Once the location of the melted nuclear fuel and the extent of structural damage are known, scientists will be able to determine the safest way to remove the fuel.

Widespread damage, thousands dead

On March 11, 2011, Japan faced a severe natural disaster in the form of the Great Sendai Earthquake and Tsunami. Japan’s main island, Honshu, experienced a powerful, 9.0 earthquake at 2:46 p.m. The earthquake resulted from a rupture in the subduction zone of the Japan trench, a deep submarine trench east of the Japanese islands. It caused widespread damage, as well as a tsunami that devastated coastal areas.

The tremors were felt as far as Petropavlovski-Kamchatsky, Russia; Kao-hsiung, Taiwan; and Beijing, China. It was followed by hundreds of powerful aftershocks over the course of the next few weeks. One of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded, the earthquake resulted in infrasonic waves that were detected by a satellite orbiting the outer edge of Earth’s atmosphere.

With a final count of approximately 18,500 people dead or missing, the Great Sendai Earthquake was one of the deadliest natural disasters in the history of Japan. Several nuclear power stations in the Tōhoku region were shut down automatically following the earthquake, and the tsunami waves damaged the backup generators at some of those plants. The plant most affected by the disaster was the Fukushima Daiichi plant. The loss of power resulted in failed cooling systems in three reactors and partial meltdowns of the fuel rods.

Melted material dripped onto containment vessels and burned holes through the floor of each vessel. This, in turn, exposed the nuclear material in the cores. The buildup of pressurized hydrogen gas resulted in the release of extreme levels of radiation and subsequent explosions.

Attempts were made to stabilize the damaged reactors by pumping seawater and boric acid into them. The area was evacuated and established as a no-fly zone in order to protect against radiation exposure.

Numerous leaks occurred at the facility over the following years. In February 2 012, the government established a cabinet-level Reconstruction Agency to coordinate rebuilding efforts in the Tōhoku region, and it was estimated that restoration efforts would take ten years. In August 2013, a major leak prompted Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority to classify it as a level three nuclear incident. In 2015, the agency reported that nearly all debris had been removed and that work had started on 75 per cent of the planned coastal infrastructure construction.