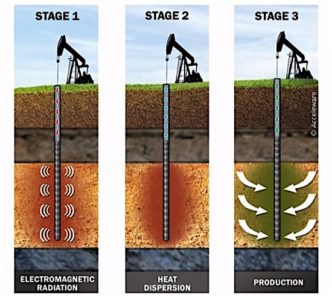

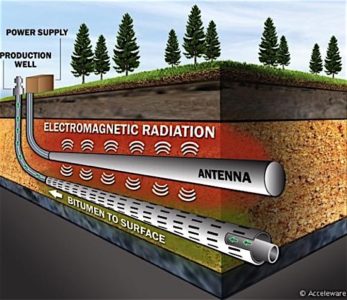

A Calgary tech company has field tested its patent-pending radio frequency heating technology, known as RF XL, developed to recover bitumen from the Alberta oil sands in an environmentally friendlier way than current steam extraction methods. Acceleware Ltd. said in a statement on March 23 that the first phase of the field test program for its enhanced oil recovery technology, undertaken in partnership with GE, has successfully achieved all of its objectives. These included demonstrating that the RF XL technology is capable of delivering high levels of power from the surface into the target formation, and that the technology can heat the test formation as efficiently and quickly as predicted. The company also said that its technology is scalable to long horizontal wells. Acceleware has sold the test data to an oil sands producer. Further tests are planned.

Radio frequency technology, which has been known and considered for down-hole heating of oil reservoirs since the 1970s but has been until now only partially successful, can improve the environmental performance of oil sands and heavy oil production significantly, Acceleware claims. Renewed interest in the technology, spurred by depletion of conventional oil reserves, better computer modeling and a deeper understanding of the technology, has brought it to the point where Acceleware can now claim that its version can reduce capital costs by 76 per cent and operating costs by 43 per cent, compared to conventional steam-injection methods (steam-assisted gravity drainage, or SAGD). RF XL requires no solvents, less land, no external water and less energy to produce oil from oil sands.

In the same way that your microwave heats your food, it heats evenly; that’s how this technology works. It’s going to heat the water in the formation and then that water is going to warm the oil and the oil will move, so the big advantage is that those radio waves travel through oil and rock evenly.

Advantages of RF heating technology also include its ability to be applied equally well in a range of different reservoir types, whether deep, shallow, thin or thick. The permeability of the heavy oil in the reservoir does not limit the amount of RF power that can be injected, and the process can be powered by green sources of electricity, the company says. The water already present in all oil reservoirs is heated by electro-magnetic energy generated by an antenna, converting it into steam.

The phase one tests, lasting three days, demonstrated that key components of RF XL are “technically sound” and the process was able to heat the test formation to steam saturation temperature within the three-day test period, with greater than 85 per cent correlation with pre-test simulations.

An Acceleware spokesman, Mike Tourigny, commented that the company expects RF XL to play an even bigger role in accessing the 90 per cent of Alberta oil sands deposits that have so far been commercially inaccessible. “The fundamental thing here is that this is a way to produce oil sands and any heavy oil with less power, which leads to less greenhouse gas and lower costs, and it is an opportunity for the Alberta oil industry specifically, but it applies to other oil deposits around the world. We are aware of the image that the oil sands have gotten as dirty oil; not only can we make that clean oil—as clean as oil can be—but we can bring some profit back to the industry.”

Tourigny likened the process to an “inside-out microwave” that heats food evenly. The radio waves heat the water in the oil formation, moving evenly through oil and rock, warming the oil and causing the oil to move.

In its statement Acceleware lists these as the five main ways in which RF XL optimizes heating for oil production:

- the system utilizes a unique RF transmission line system that is able to carry high levels of RF power

- the transmission line system is highly efficient

- the system delivers heat to the formation quickly after start-up

- the system employs a highly efficient silicon carbide (SiC) based RF power generator

- the technology is scalable to very long horizontal wells

The technology remains three to five years away from commercial use.