Disruption is a common theme running through two recent reports on prosperity in Canada, one from the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, the other from the federal government’s top advisor on economic growth. The OCC report observes that business prosperity in Ontario and elsewhere is being challenged by rapid breakthroughs in areas of technology such as artificial intelligence, which are disrupting global industry and reducing the need for workers in certain sectors. The federal advisor’s report, meanwhile, stresses that Canada needs to prepare its workers for “major structural changes” that include the automation of jobs and the growth of the so-called gig, or temporary contract, economy. Both reports call for strong, decisive government action to ensure that businesses have access to the skilled workers they need to flourish in the knowledge-driven economy.

The OCC report points to the puzzling reality that while most Ontario businesses are confident in their own prospects for profitability and growth, they do not feel the same confidence in the province’s economic outlook, a situation it refers to as a “confidence gap.” Paradoxically, business confidence is quite high in Ontario—48.5 per cent, a fifteen-year high—as measured by the OCC’s Business Prosperity Index. The higher the index reading, generally speaking, the better the business is doing. But the index does not tell the whole story.

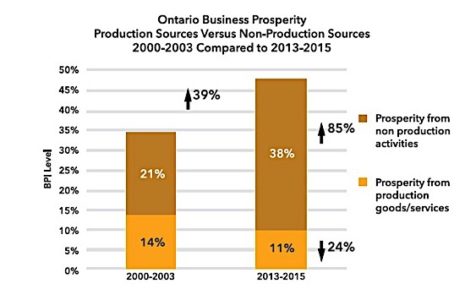

First, the OCC is concerned that the percentage of business prosperity being generated by “production sources” like manufacturing has been steadily falling, while non-production activities, such as financial services, have been rising. A consequence of this trend could be lower investment levels in production-related businesses, which cannot provide the higher returns associated with non-production businesses.

An even bigger challenge for businesses is workforce development. While employment numbers appear good in Ontario, with an unemployment rate below the national average and projections of high job creation over the next three years, most businesses have difficulty recruiting qualified workers. This problem, says the OCC report, is a result of the changing nature of work itself—that disruptive “fourth industrial revolution” of artificial intelligence and automation that is sweeping the world and leaving so many workers out in the cold—and of something much more basic: the aging of the population.

A critical threat facing OCC members is that of staffing, and the difficulty (or even outright inability) of hiring the right people for the right job. Among those who attempted to recruit a new staff member in the past 6 months, only 14 per cent did not encounter any challenges in the process. More than half also reported that the size of their workforce has remained the same for the past six months, and 61 per centr expect to keep the same size of workforce in the next six months. Understandably, 53 per cent of members ranked “acquiring suitable staff” as a top-three influencer of organizational health.

Without the right employees, businesses will find it difficult to increase their prosperity through growth in production-generating activities, the report says. Continued prosperity in the province will be “highly dependent” on policy measures that ensure a supply of “creative, flexible, highly-skilled” workers.

At the federal level, the special economic advisor to the minister of finance warns that 40 per cent of existing Canadian jobs, many held by older workers, could disappear over the next ten years due to automation. Fully two-thirds of existing economic activity, especially work of a repetitive, physical nature, could be automated with existing technologies, he says, even before the new wave of automation arrives. At highest risk are lower-skill, lower-income workers.

Even before automation takes off, it is estimated that two-thirds of current economic activity could be automated with existing technologies. This will only accelerate: advances in automation and “smart” technologies could affect nearly half of current jobs in Canada . . . Lower-skill, lower-income workers will experience a disproportionate share of the impact. Occupations that mostly require predictable physical work, or rote and repetitive knowledge are most likely to be automated. Artificial intelligence could also automate significant chunks of repetitive higher-skill jobs like accounting. These trends create an imperative for aligned and efficient efforts to mitigate and minimize job displacement for Canadians in rapidly transforming industries, as well as setting up future generations for work success.

Worryingly, Canada does not currently have an “overarching strategy” to deal with this impending job dislocation, according to Dominic Barton’s “The Path to Prosperity,” prepared with the Advisory Council on Economic Growth. At the top of the list of recommendations in the report, are the need for companies to be more innovative and productive, and the need for building a highly skilled and “resilient” workforce that can adapt to technological change.

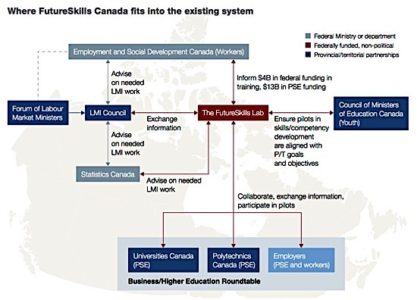

For the latter, he recommends the creation of a FutureSkills Lab, described as a non-profit, non-political body that would promote next generation skills development. Among its main functions would be financing workers’ skills and competency development based on labour market needs.

Other recommendations include streamlining immigration to allow “top talent” easier entry into Canada, and increasing the availability of growth capital and financial advice to help companies to scale up. Innovation is critical, and this is an area in which Canada is weak. While the country has a successful “innovation ecosystem,” with plenty of talent, large firms and high-growth SMEs, its efforts are “subscale,” in that there is insufficient collaboration among stakeholders and a poor record of scaling up among smaller companies.

The Barton report takes a generally traditionalist view of Canada’s economic role in the world, referring to the country as “a small trading nation.” With abundant natural resources and a highly educated workforce, it has the tools to ride the next wave of global change. However, the country can no longer rely exclusively on commodities, one of the traditional engines of growth, but must focus on innovation and productivity.

The country should be positioned as a global trading hub, and should strengthen its trading ties with other countries, including China, Japan and India, as well as within NAFTA.

Canada’s many core strengths include agriculture and food, energy and renewables, mining and metals, health care and life sciences, advanced manufacturing, financial services, tourism and education. Much of the potential of these key sectors is held back, however, by “excessive regulation,” shortages of skilled labour, and inadequate infrastructure. Barton says the government must work with the private sector to remove such barriers to growth and unleash the full potential of these key sectors.