If solar cells were, say, 30 per cent more efficient than they currently are, the number of panels needed to convert light to electricity would be reduced, with a corresponding reduction in the cost of installing them. The amount of roof space or open land needed to accommodate solar panels could be reduced as well. Solar power could be made less expensive all around if more power could be “coaxed” out of each solar cell. And the University of California, Riverside, says that a “huge gain” in this direction has been made by a team of its researchers.

The “ingenious” process makes use of infrared light from the sun, a region of the spectrum that normally passes through photovoltaic materials without benefit. The researchers say they have devised a process by which solar panels could potentially be made up to 30 per cent more efficient and reduce the amount of light that is now wasted in conventional photovoltaics.

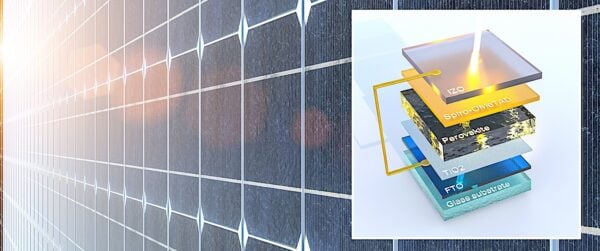

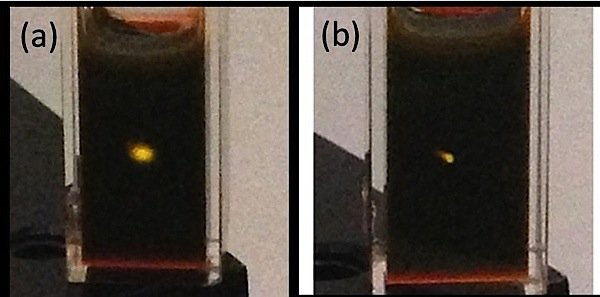

The process involves “upconverting” two low-energy photons, one from the visible and one from the near-infrared spectral regions, into one high-energy photon. Writing in the journal Nano Letters, the researchers describe how semiconductor nanocrystals are combined with molecular emitters to upconvert the photons. It is the combination of inorganic nanocrystals and organic compounds that makes the process possible, according to lead researcher Christopher Bardeen. He said that the key to their research is the hybrid composite material. Organic compounds cannot absorb in the infrared but are good at combining two lower energy photons to a higher energy photon. “Put simply, the inorganics in the composite material take light in; the organics get light out.”

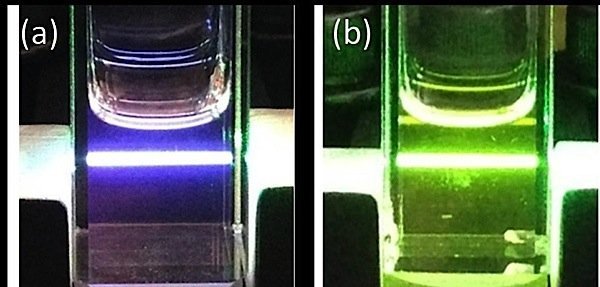

In the photo above, from UC Riverside, upconversion is taking place in the violet-coloured cuvette on the left, and no upconversion in the green. According to the university, “this indicates the enhancement of the unconverted fluorescence.”

According to Bardeen, the materials are “reshaping the solar spectrum” so that it better matches the materials used in solar cells. The university says that the inorganic materials Bardeen and co-researcher Ming Lee Tang used were cadmium selenide and lead selenide semiconductor nanocrystals. The organic compounds they used to prepare the hybrids were diphenylanthracene and rubrene. The cadmium selenide nanocrystals could convert visible wavelengths to ultraviolet photons, while the lead selenide nanocrystals could convert near-infrared photons to visible photons.

The process has potential applications in biological imaging, data storage and organic light-emitting diodes. By varying the combinations of nanocrystals and emitters—the inorganic and organic components—researchers can vary the emission wavelengths, giving the process great flexibility.