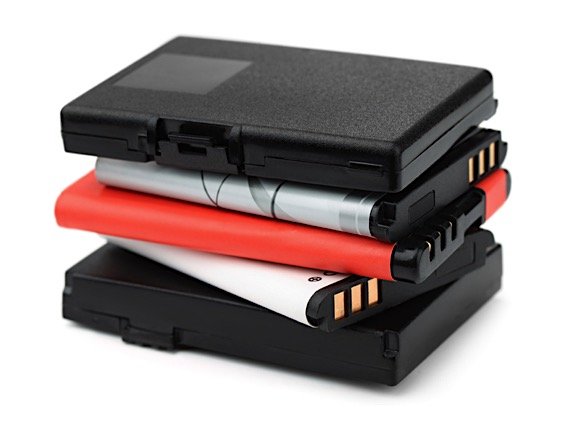

Since their introduction in the late 1990s, lithium ion batteries have been used in numerous devices that are used in everyday life. Some of the devices which utilize these batteries include laptop computers, mobile phones, medical devices, and various toys and gadgets found around the house and in offices.

However, lithium ion batteries are not perfect. Performance may decay over time, the batteries may not fully charge after a certain number of cycles, and they may discharge quickly even when idle. Researchers from the University of Illinois applied a technique using 3-D X-ray tomography of an electrode to better understand the inner workings of a lithium ion battery in the hopes of building batteries with greater storage capacity and longer life spans.

Lithium ions embed themselves into host particles that reside in the battery anode electrode and are stored there until needed. “Every time a battery is charged, the lithium ions enter the graphite, causing it to expand by about 10 percent in size, which puts a lot of stress on the graphite particles,” said University of Illinois Professor and Director of the Advanced Materials Testing and Evaluation Laboratory John Lambros. “As this expansion-contraction process continues with each successive charge-discharge cycle of the battery, the host particles begin to fragment and lose their capacity to store the lithium and may also separate from the surrounding matrix leading to loss of conductivity.”

“If we can determine how the graphite particles fail in the interior of the electrode, we may be able to suppress these problems and learn how to extend the life of the battery. So, we wanted to see in a working anode how the graphite particles expand when the lithium enters them. You can certainly let the process happen and then measure how much the electrode grows to see the global strain, but with the X-rays we can look inside the electrode and get internal local measurements of expansion as lithiation progresses.”

The team custom built a rechargeable lithium cell that was transparent to X-rays. They then added graphite and zirconia particles. “The zirconia particles are inert to lithiation; they don’t absorb or store any lithium ions,” said Lambros. “However, for our experiment, the zirconia particles are indispensable: they serve as markers that show up as little dots in the X-rays which we can then track in subsequent X-ray scans to measure how much the electrode deformed at each point in its interior.”

Lambros stated that internal changes in the volume are measured using a Digital Volume Correlation routine, an algorithm in a computer code that is used to compare the X-ray images before and after lithiation.

The software was created about 10 years ago by Mark Gates, a University of Illinoiscomputer science doctoral student co-advised by Lambros and Michael Heath. Gates improved upon existing DVC schemes through critical changes that were made to the algorithm. Rather than only being able to solve very small-scale problems with a limited amount of data, Gates incorporated parallel computations that ran multiple parts of the program simultaneously and produced results in a fraction of the time over multiple points of measurement.

“Our code runs much faster,” said Lambros. “Instead of just a few data points, it allows us to get about 150,000 data points, or measurement locations, inside the electrode. It also gives us an extremely high resolution and high fidelity.” According to Lambros, only a handful of research groups use this technique. “Digital Volume Correlation programs are now available commercially, so they may become more common. We’ve been using this technique for a decade now, but the novelty of this study is that we applied this technique that allows internal 3-D measurement of strain to functioning battery electrodes to quantify their internal degradation.”