Anyone with an interest in trade policy in Canada can be forgiven for feeling bewildered by the contradictory claims made by politicians, labour and industry leaders, and other commentators regarding the benefits of free trade agreements. One of the biggest free trade agreement to which Canada has committed, the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), has divided Canadians and Americans alike. In the ongoing US presidential campaign, all of the major candidates in both parties have said they are opposed to the TPP. Even Hillary Clinton, who was involved in negotiating the deal, is now against it. But the current administration continues to tout the economic benefits of the deal as “overwhelming.”

According to Bernie Sanders, the TPP is another in a line of failed deals that have cost “millions of jobs and closed tens of thousands of factories” in the US. Donald Trump said the deal is “terrible.”

Canada, like the US has pursued free trade agreements (FTAs) aggressively over the past decade, seeing them as a “magic bullet” for Canada’s trade ailments. Ten new FTAs were concluded between 2006 and 2015. But an economics professor at McMaster University who has ties to Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector trade union, argues in a paper for the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) that Canada should not be signing more free trade deals, which have not boosted the quality and quantity of trade, as promised. On the contrary, they have contributed to what Jim Stanford calls a “sustained deterioration” in Canada’s international trade performance. Growth in exports of Canada’s goods and services has been among the weakest of any industrialized country, he says, shifting to more resource-based products and away from “more sophisticated, higher-value goods and services.”

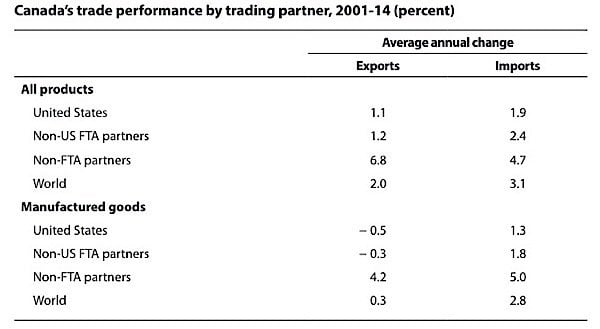

In short, Canada has pursued trade liberalization more aggressively, on more fronts, than ever before, yet its trade performance has continued to deteriorate. Moreover, this deterioration has been more marked in bilateral trade flows between Canada and its FTA partners than with its trade with the rest of the world. Such results raise a critical question: Is signing more FTAs really the best way to address Canada’s trade woes, or has it actually been part of the problem?

What’s more, the deterioration in trade has been more pronounced in bilateral trade flows between Canada and its FTA partners than with the rest of the world. Whereas exports grew by an average 6.5 per cent per year between 1981 and 2001, since then growth has been just 1.1 per cent per year. Canada is ranked second from last among the thirty-four OECD countries (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) for growth in exports. The OECD average growth rate from 2001 to 2015 was 3.6 per cent: Canada’s average growth was 0.7 per cent.

A “deindustrializing” of Canada’s economy has been taking place, Stanford argues, as innovation activity has fallen and spending on research and development has declined to its lowest level ever recorded in 2015.

Rather than continue to pursue more FTAs, which, Stanford claims, are harmful to an economy that is not adequately competitive in trade both on cost and in providing high-quality, innovative goods, Canada’s highest priority should be to support “globally oriented, innovative, technology-intensive domestic firms that can develop, produce and sell the high-value goods and services foreign purchasers demand.” Canada will continue to lose global trade share, he says, unless it positions itself as a product and process innovator.