For engineers and designers specifying materials for the next generation of EVs, defense systems, and grid-scale batteries, the critical minerals supply chain has long been a black box. You know the performance specs for nickel-rich cathodes or superalloys, but the geopolitical and environmental cost of getting that nickel from ore to finished component has been notoriously difficult to quantify. A discovery in Newfoundland is promising to change that equation by introducing a new variable: awaruite, a naturally occurring, magnetic nickel-iron-cobalt alloy that completely bypasses the need for conventional—and foreign-dominated—smelting.

First Atlantic Nickel Corp. (TSX-V: FAN | OTCQB: FANCF) is advancing its Pipestone XL Nickel Alloy Project, a district-scale system spanning 30 kilometers across a top-tier mining jurisdiction. While the project is still in the exploration and development phase, its implications for North American manufacturing, mineral processing, and environmental design are profound. This isn’t just another nickel sulfide discovery; it’s a fundamental shift in the type of resource being developed, one that aligns with the urgent need for a secure, sustainable, and technologically compatible domestic supply chain.¹

The Strategic Chokepoint: Why Smelting Defines the Crisis

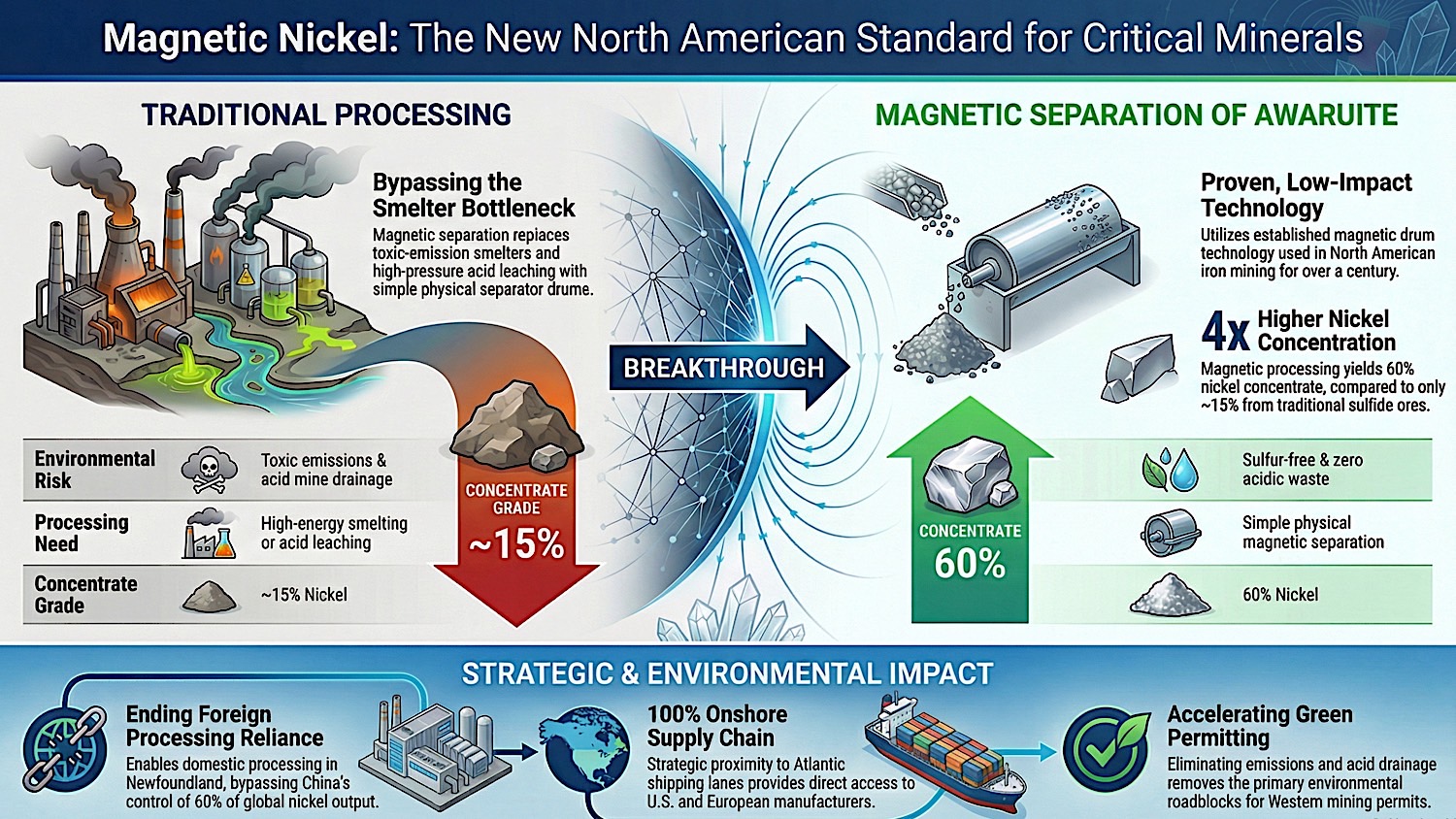

To understand why awaruite matters, one must first understand the critical vulnerability in the North American nickel supply chain. The United States currently has no active nickel smelters. Its only operating nickel mine, the Eagle Mine in Michigan, is scheduled to deplete its reserves in the near future. This forces any domestically mined sulfide ore to be exported for processing, creating a strategic vulnerability.²

Meanwhile, global processing capacity is overwhelmingly concentrated in a single sphere of influence. As highlighted at Benchmark Week 2025, where First Atlantic recently showcased its project, China’s dominance is absolute. Chinese entities operate or finance a vast network of smelters in Indonesia, which alone accounts for roughly half of world nickel production. This control extends through the entire value chain, from mining to the production of nickel sulfate for batteries.³ According to the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, this creates a “dangerous exposure” for Western aerospace, defense, and clean-energy sectors.⁴

Awaruite: The Mineral That Skips the Smelter

Enter awaruite (Ni₃Fe). Unlike conventional nickel minerals like pentlandite (a sulfide) or laterites (oxides), awaruite is a natural alloy. It typically contains approximately 75-77% nickel, alloyed with iron and cobalt, and is completely free of sulfur.²

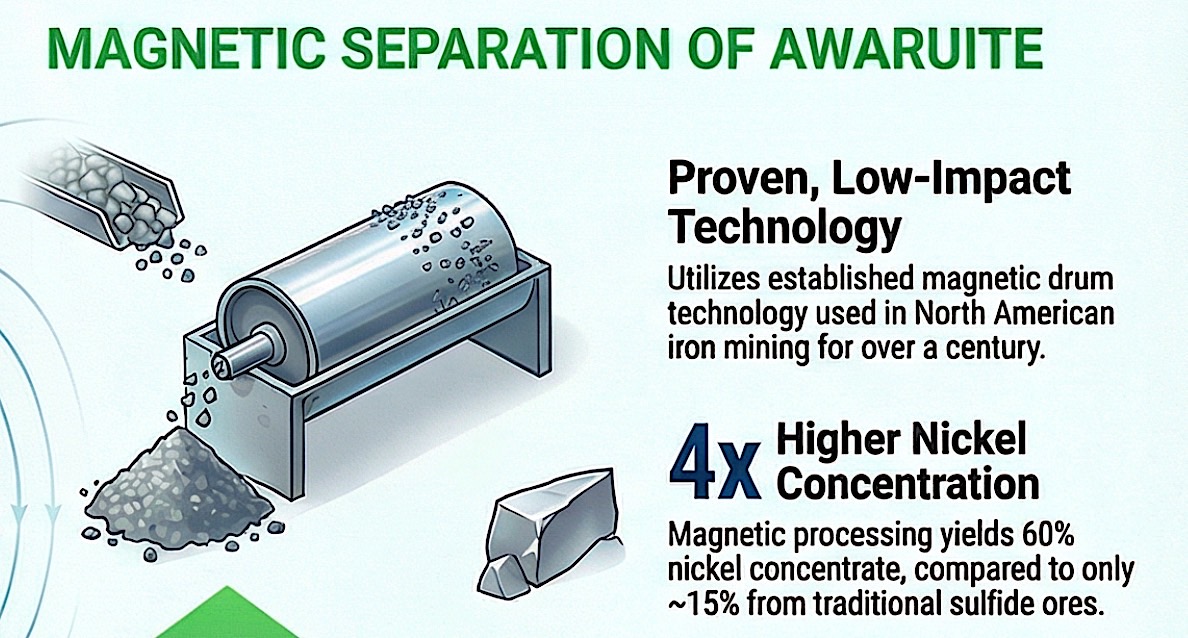

It is this fundamental metallurgy that dictates its revolutionary processing path. Because awaruite is naturally magnetic, it can be concentrated using simple, low-tech magnetic separators. This is the same technology used in North American iron ore operations for over a century. The process eliminates the need for the energy-intensive, high-emission smelting step required to break the chemical bonds in sulfides, or the high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) used for laterites.

As the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) noted as far back as 2012, “The development of awaruite deposits in other parts of Canada may help alleviate any prolonged shortage of nickel concentrate. Awaruite, a natural iron-nickel alloy, is much easier to concentrate than pentlandite, the principal sulfide of nickel.”⁵

The Processing Flowsheet: From Magnetic Drum to High-Grade Concentrate

For the engineering community, the proposed processing flowsheet at Pipestone XL offers a compelling case study in efficiency. Metallurgical testing, including Davis Tube Recovery (DTR) on drill core from the RPM Zone, has validated a two-stage process that is both proven and scalable.²

Stage 1: Magnetic Separation. The ore is crushed and ground, then fed through magnetic drum separators. The awaruite is pulled out, achieving a mass pull of approximately 9%. This means 90% of the material (the gangue) is rejected immediately, without chemicals, drastically reducing the volume requiring further processing. The resulting magnetic concentrate grades average 1.38% nickel, which is already a significant upgrade from the run-of-mill ore.²

Stage 2: Flotation to Premium Concentrate. The awaruite concentrate then enters a conventional froth flotation circuit. Research presented at the XXXI International Mineral Processing Congress (IMPC) in 2024 confirms that awaruite responds exceptionally well to flotation with xanthate collectors, allowing for selective separation from other magnetic minerals like magnetite.⁶ This second stage upgrades the nickel content dramatically.

The end product is a high-grade concentrate that can exceed 60% nickel.² Crucially, this concentrate is also free of penalty elements often found in sulfides (like arsenic or magnesium), making it a premium feedstock for nickel sulfate producers and stainless steel mills. As FPX Nickel, another developer of awaruite deposits, has demonstrated in pilot testing, this concentrate can be fed directly into hydrometallurgical processes to produce battery-grade nickel sulphate.⁷

Technical Implications for North American Manufacturing

The ability to produce a high-grade, clean nickel concentrate onshore has direct implications for engineers downstream.

- Feedstock Security for Battery Materials: With the Inflation Reduction Act tying EV tax credits to domestic sourcing, automakers need a secure, traceable supply of nickel. The Pipestone XL project could supply the feedstock for emerging U.S. refineries, such as the Westwin Elements refinery in Oklahoma, which recently signed offtake agreements worth over $1.4 billion for high-purity Class 1 nickel.⁸

- A Domestic Source of Chromium: The Pipestone XL deposit isn’t just about nickel. The ultramafic complex is also enriched in chromium. The magnetic concentrate produced in testing averaged 1.67% chromium.² The U.S. has not mined chromium since 1962, despite the USGS declaring there is “no substitute” for it in stainless steel and superalloys.⁹ This project could provide a much-needed domestic source of this critical mineral.

- Cobalt Integration: Cobalt, often associated with nickel in sulfide deposits, is also present in the awaruite alloy. This means a single concentrate stream could deliver three critical minerals—nickel, cobalt, and chromium—simplifying the supply chain for manufacturers of stainless steel and specialty alloys.²

The Environmental Impact: Designing for a Lower Carbon Footprint

For engineers focused on lifecycle analysis and sustainable design, the environmental advantages of awaruite processing are as significant as its geopolitical ones. Traditional nickel processing has a heavy environmental toll.

- Elimination of SO₂ Emissions: Sulfide smelting releases sulfur dioxide, a cause of acid rain, which requires expensive capture and treatment (e.g., producing sulfuric acid as a byproduct). Awaruite contains no sulfur, so this entire emissions stream is designed out of the process.²

- No Acid Mine Drainage: One of the longest-lasting environmental liabilities of sulfide mines is acid mine drainage (AMD), where exposed sulfides react with water and air to produce sulfuric acid, leaching heavy metals. Because awaruite is sulfur-free, it presents a dramatically lower risk of AMD, potentially easing permitting and long-term closure costs.²

- Lower Energy Intensity: Smelting is an energy-intensive, high-temperature process. By replacing it with mechanical separation (magnetic and flotation), the overall energy profile of producing a nickel concentrate is significantly reduced. This aligns with the goals of manufacturers seeking to lower Scope 3 emissions in their supply chains. Furthermore, the project’s location in Newfoundland provides access to clean hydroelectric power, offering a pathway to a very low-carbon nickel product.¹

A New District, A New Paradigm

The scale of the Pipestone XL project is also critical. It is not an isolated occurrence. First Atlantic has consolidated 100% ownership of the entire 30-kilometer Pipestone Ophiolite Complex, with multiple confirmed zones of awaruite mineralization including the RPM, Super Gulp, and historic Atlantic Lake zones. Drilling at the RPM Zone has intersected mineralization from surface to depths of nearly 500 meters, with intervals of over 447 meters returning consistent, recoverable nickel grades.² The Phase 2X drilling program is specifically designed to double the footprint of this known mineralization, underscoring the district-scale potential.

This scale is essential. The demand projections are staggering. Global nickel demand is expected to double by 2040, requiring the equivalent of 60 new mines by 2030.¹⁰ Tesla’s expansion of its Nevada gigafactory alone could require over 375,000 tons of nickel per year—the output of nine average-sized mines.² The development of awaruite districts like Pipestone XL, combined with other major projects like Canada Nickel Company’s Crawford project in Ontario which is being fast-tracked by the provincial government, signals the emergence of a new, resilient North American nickel belt.¹¹

For the engineers and designers who will build the next generation of technology, the message is clear: a new class of nickel is entering the market. It is a material that arrives with a different industrial DNA—one that is less energy-intensive, free of smelting, and rich in multiple critical elements. The rediscovery of awaruite isn’t just a mining story; it is the foundation for a redesigned, more secure, and more sustainable North American supply chain.

References

- First Atlantic Nickel Corp. “THIS RARE EARTH NICKEL-COBALT ALLOY & CHROMIUM DISCOVERY COULD TRANSFORM NORTH AMERICA’S CRITICAL MINERAL SUPPLY CHAIN.” fanickel.com, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fanickel.com/Ni3Fe. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- First Atlantic Nickel Corp. “First Atlantic Nickel Attends Benchmark Week 2025 Conference Highlighting Awaruite, a Naturally Magnetic Nickel-Cobalt Alloy, as a Smelter-Free Source for North America’s Critical Minerals.” Globe Newswire via Financial Post, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://financialpost.com/globe-newswire/first-atlantic-nickel-attends-benchmark-week-2025-conference-highlighting-awaruite-a-naturally-magnetic-nickel-cobalt-alloy-as-a-smelter-free-source-for-north-americas-critical-minerals-s. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- International Energy Agency (IEA). “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024.” iea.org, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2024. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- Gulley, A.L. “China’s Nickel Diplomacy: Controlling the Supply Chain for Strategic Advantage.” U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, 2023.

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). “Mineral Commodity Summaries: Nickel.” usgs.gov, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2012/. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- Smith, J.R., et al. “Flotation Characteristics of Natural Awaruite (Ni₃Fe) from Ultramafic Complexes.” Proceedings of the XXXI International Mineral Processing Congress (IMPC), Washington, D.C., 2024, pp. 412-425.

- FPX Nickel Corp. “Decar Nickel District: Metallurgical Testing Confirms Production of High-Grade Nickel Sulphate.” fpxnickel.com, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.fpxnickel.com/news/. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- Westwin Elements. “Westwin Elements Secures Over $1.4 Billion in Binding Offtake Agreements for High-Purity Nickel.” westwinelements.com, Jan. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.westwinelements.com/news. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). “Mineral Commodity Summaries: Chromium.” usgs.gov, Jan. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- Fraser Institute. “Annual Survey of Mining Companies: 2024.” fraserinstitute.org, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/annual-survey-of-mining-companies-2024. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].

- Government of Ontario. “Ontario Fast-Tracks Critical Minerals Projects to Strengthen EV Supply Chain.” news.ontario.ca, Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/. [Accessed: Feb. 19, 2026].