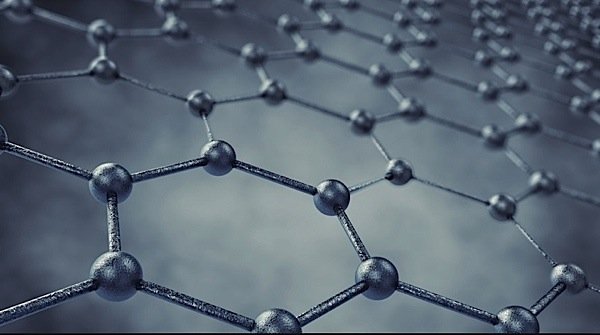

A team of British researchers led by Nobel prize winner Sir Andre Geim has published new findings about graphene that could have revolutionary effects on fuel cell technology. Geim was the first to isolate graphene, in 2004, for which he was given the Nobel Prize in physics. Graphens is a one-atom thick material that is renowned for its strength—it is said to be 200 times stronger than steel—and for its impermeability, which make it ideal for applications such as corrosion-proof coatings and impenetrable packaging.

Geim and his team found that protons, contrary to expectations, are not repelled by graphene. The University of Manchester, where the research was carried out, released a statement that explains how impenetrable graphene is. “It would take the lifetime of the universe for hydrogen, the smallest of all atoms, to pierce a graphene monolayer,” the statement said. The scientists therefore fully expected that it would be as impenetrable to protons as well. Instead, they found that hydrogen protons pass through the ultra-thin graphene crystals “surprisingly easily.” This occurred more smoothly at raised temperatures or when the graphene layer was coated with platinum nanoparticles, acting as a catalyst.

The discovery makes monolayers of graphene “attractive” for use in proton-conducting membranes, which are necessary for fuel cell technology. Hydrogen fuel cells work by converting the chemical reaction between oxygen and hydrogen into electricity, but in most fuel cells, the two fuels contaminate one another by “fuel crossover” through the membrane. “Without membranes that allow an exclusive flow of protons but prevent other species to pass through, this technology would not exist,” said Geim.

The graphene membranes can also be used to extract hydrogen from a humid atmosphere, which leads the researchers to hypothesise that this harvesting of hydrogen could be combined with the fuel cell technology to create a mobile electric generator fueled by hydrogen in the air. “Essentially, you pump your fuel from the atmosphere and get electricity out of it,” Geim said, adding that the team’s study provides proof that this type of device is possible.