The World Economic Forum (WEF) is encouraging big investors to reconsider renewable energy, particularly solar, as a viable, profitable asset class. Renewable energy technology has made “exponential gains” in efficiency, it says, making it more and more competitive economically. Many countries that have invested heavily in renewable energy have already achieved grid parity, wherein the cost of electricity from renewables is equal to or less than the cost of grid electricity. Renewable energy technology has reached an inflexion point with respect to cost-effectiveness, says the WEF report, with further improvements expected to come even faster. As technology continues to improve, economies of scale will encourage wider adoption, which will in turn stimulate demand, setting up a self-reinforcing process which will be relatively low-risk for investors.

The costs of producing solar panels having fallen by about 20 per cent in the last five years, and the WEF forecasts that by 2020 electricity generated from solar photovoltaic sources will cost less, worldwide, than coal-or gas-generated electricity. Until now, renewable energy has been viewed by many as “frontier technology,” fraught with risks for cautious investors. Now, argues the WEF, it has become solidly mainstream, and will grow even more so.

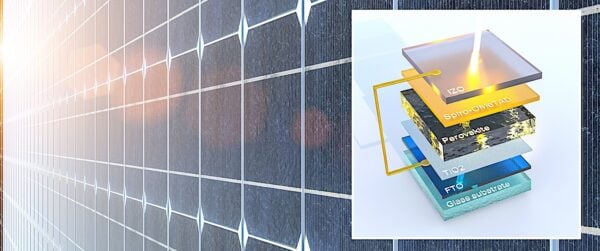

Importantly, solar photovoltaics are also becoming more efficient at converting sunlight into usable electricity. The efficiency rating of most PVs was “stagnant” at 15–22 per cent for many years, but researchers have reported up to 46 per cent efficiency in lab tests. Greater efficiency will make solar panels even more attractive to consumers, and adoption rates will increase, as fewer solar panels will be needed to achieve the same electricity output.

Even though the renewables proposition has always had environmental appeal, technology has historically been subpar in delivering appropriate returns to investors without an impact mandate. Inefficiencies in incipient solar and wind technologies have perpetuated a global energy matrix that still features coal and natural gas accounting for 62 per cent of total generation. Nonetheless, exponential improvements in renewable technology, both in efficiency and cost, have made renewable energy competitive in the past few years.

While the WEF sees renewable as a good investment opportunity, that investment remains relatively small: just 0.4 per cent of assets under management by the world’s top 500 asset owners are identified as low-carbon ($138 billion out of $38 trillion). If the world is to meet the goal of holding global warming to 2 degrees, established at the Paris climate talks of December 2015, it will need to invest $1 trillion a year in renewables by 2030. Current investment is sitting at around $200 billion, it says.

According to the German Solar Association, the world’s total installed solar power capacity has now reached 300 gigawatts. In 2016 alone, 70 gigawatts of new solar power, enough to supply 25 million households with 3600 kilowatt hours of electricity, was installed. Canada is ranked in the top ten countries around the world for its attractiveness to investors in renewable energy. In 2014, Canada was ranked fourth in the world for renewable electricity capacity.

Ironically, a major problem that has dogged the solar industry from an environmental perspective is that of emissions. While the use of solar panels creates no emissions, the fossil-fuel intensive production process does. The silicon that coats most solar panels must be melted in furnaces at over 1400 degrees Celsius, creating huge amounts of emissions.

However, researchers in the Netherlands say they have found that the breakeven point for solar panels—the point at which the disadvantages of photovoltaics, as measured by total worldwide emissions created in producing them, and their benefits, mainly the emissions saved by using them, converge—may already have occurred. They found that PV modules manufactured today are responsible for an average of 20 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour of electricity produced over their 30-year life span. Panels produced in the 1970s, in contrast, produced from 400 to 500 grams per kWh. The break-even point, when energy output equals manufacturing energy input, has fallen from 20 years to just two years. As well, each time the world’s solar capacity doubles, the energy and CO2 emissions associated with making them fall by up to 24 per cent.