Manufacturers in Canada took orders, bought raw materials and raised production levels in February at the fastest rate in more than two years. The robust and accelerated growth contributed to a sustained recovery in job creation and business confidence in the manufacturing sector, according to the latest IHS Markit report.

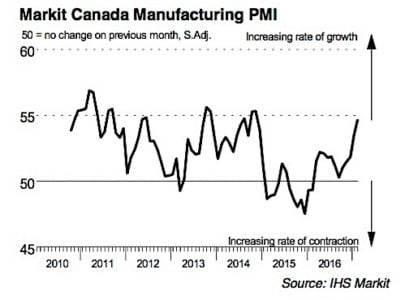

The Markit Canada Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ index (PMI) rose to 54.7 in February, up from 53.5 in January. This was the strongest improvement since November, 2014 and the highest quarterly figure for over two years. IHS Markit says that faster rates of output and new business growth were the main factors boosting the expansion. Greater domestic demand, especially in the energy sector, is credited with much of the improvement in manufacturing growth. Rising spending by companies in the energy sector led to a “surge” in manufacturing across Alberta and B.C., with production volumes expanding at the fastest pace since 2010, according to IHS Markit economist Tim Moore.

Export sales growth, however, remained “subdued,” and contributed only marginally to new business gains.

The Markit survey also shows a rebound in confidence in the manufacturing sector, the degree of positive sentiment reaching its strongest in three years. Manufacturers sought to boost their stocks of finished goods in the expectation of higher sales, putting pressure on supply chains with higher demand for inputs. The higher level of business confidence also led to the greatest increase in employment in February in over two years.

The manufacturing sector has improved since the financial crisis of 2008-09, though it has declined as a proportion of the overall economy. This is common to every major developed country. Manufacturing now accounts for about 10 per cent of Canada’s GDP and half of all exports.

The director of Canadian Industrial Outlook, Michael Burt, wrote recently that further decline is not inevitable, as shown by the success of Canada’s food production industry, which has shown the strongest growth in the manufacturing sector since the year 2000. It has done so by taking advantage of growing demand in international markets, and by product innovation. Other manufacturers can have similar success, Burt argues, if they fit into the value chains of larger, global firms, even if that means shifting part of their production into other countries.

They also need to focus on specialising in high-value manufacturing segments, and integrating client services, such as ongoing maintenance, quality upgrades, product tracking and monitoring, and sophisticated trouble-shooting, into the sale of manufactured goods to improve competitiveness. Ultimately, says Burt, Canadian manufacturing’s future will depend on “building products differently,” with innovation driving the productivity improvements needed for the sector to remain competitive.

Investment in research and development is also generally very low, Burt says, with the notable exceptions of aerospace, pharmaceuticals, and electronics. This low investment in R&D also contributes to a decline in global competitiveness.