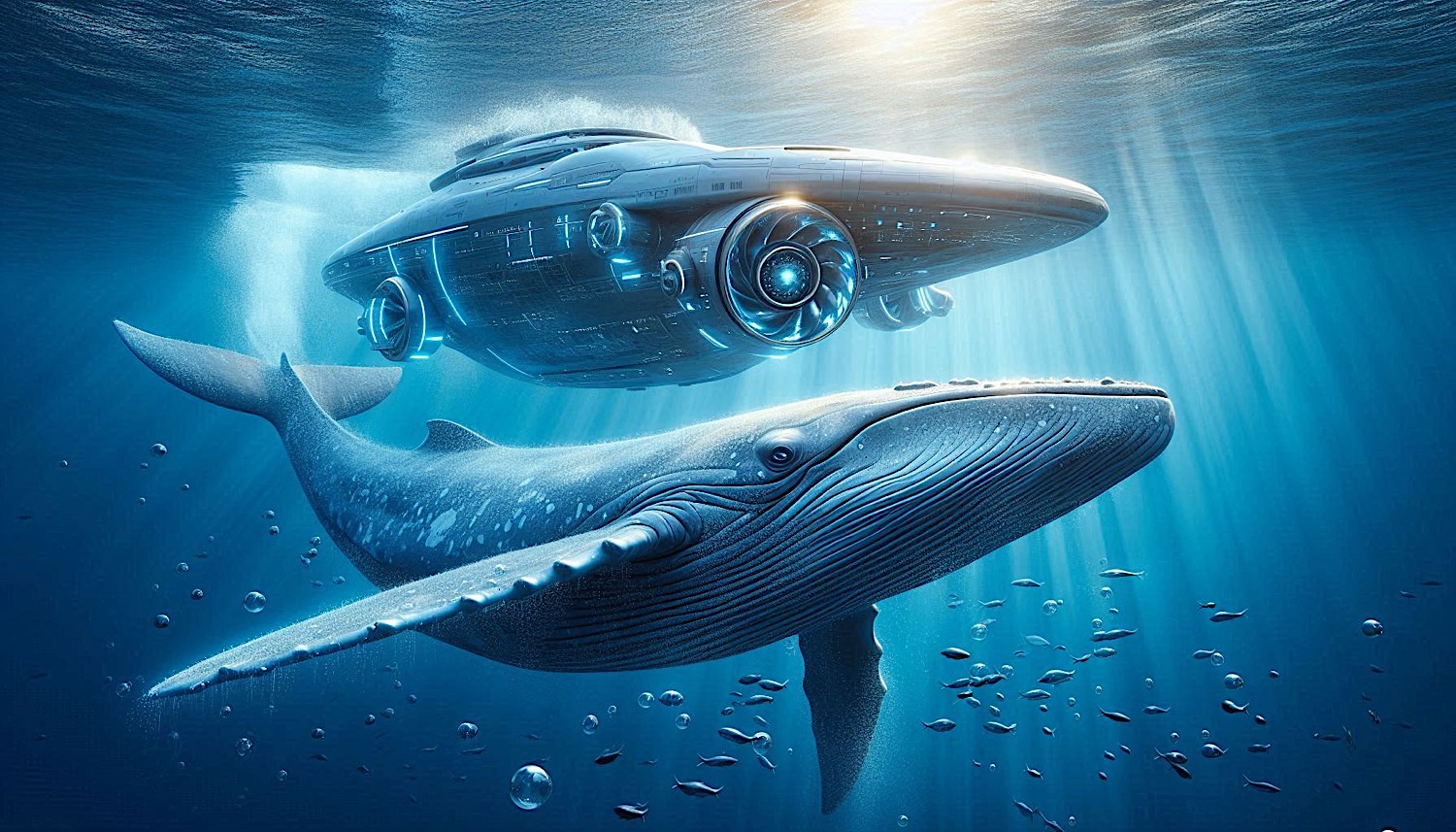

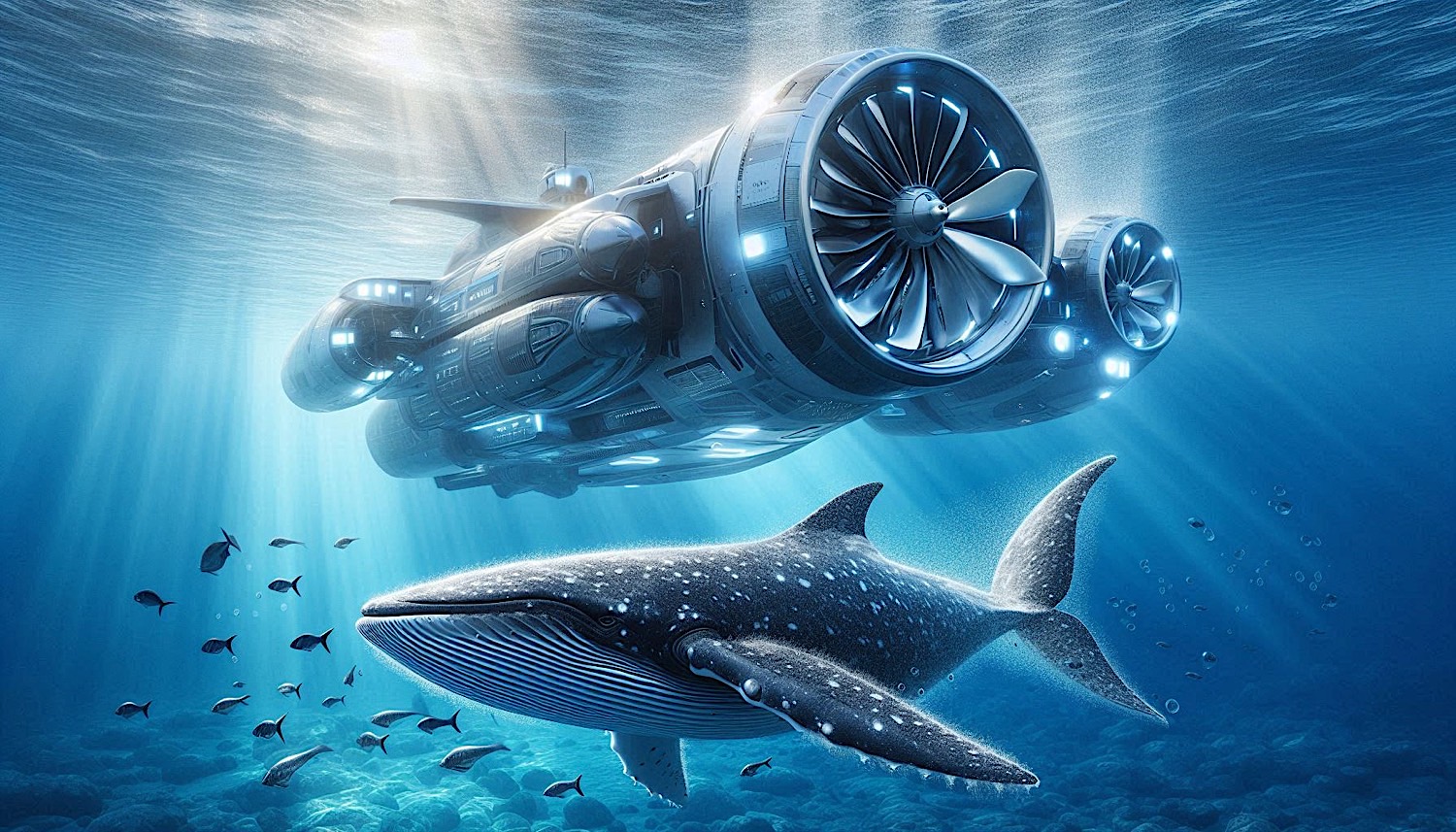

From cavitation tunnels to dimpled blade tips, breakthrough research aims to quiet the world’s fleet without sacrificing speed or efficiency — to help save marine life.

Context: The Ocean’s Overlooked Pollutant

When we think of pollution from ships, we picture oil slicks, bilge discharge, or plumes of black smoke. But there is another form of pollution, invisible to the human eye, that travels for hundreds of miles through the ocean: noise.

Commercial shipping has transformed the underwater soundscape. The constant churn of propellers creates a low-frequency din that masks the calls of whales, disrupts the echolocation of dolphins, and interferes with the feeding and mating patterns of countless marine species. For decades, this has been an accepted cost of global trade.

But a quiet revolution is underway. Engineers are finally tackling the root cause of propeller noise—a physical phenomenon called cavitation—with the goal of making the world’s fleet quieter without forcing ships to slow down. And the latest research suggests they are getting close.

Section 1: The Physics of the Problem – Understanding Cavitation

To understand how to quiet a propeller, you first have to understand cavitation. It is a deceptively simple phenomenon with violently complex consequences.

As a propeller blade spins, the pressure on its suction side (the forward-facing surface) drops dramatically. When this pressure falls below the vapor pressure of water, the water literally vaporizes, forming tiny bubbles. These bubbles are carried along the blade and into the wake. When they encounter a region of higher pressure, they collapse with astonishing force.

This collapse is the source of the noise. It creates a sharp, impulsive sound that can exceed 180 decibels underwater and travel for hundreds of miles. For marine mammals that rely on sound as their primary sense, this is like trying to hold a conversation next to a jackhammer.

Leonie Föhring, a doctoral researcher at HAW Kiel’s Institute for Shipbuilding and Maritime Technology, is spending her days watching this process unfold. Using a cavitation tunnel, high-speed cameras, and underwater microphones, she is capturing the birth and death of these bubbles in microscopic detail .

“The loud impulse occurs at the moment the bubble collapses,” Föhring explains. “Its volume depends on how rapidly the process takes place. We now want to find out whether it’s even possible to slow this collapse down—and how propellers would need to be designed to achieve that” .

This is the core question of the MinKav project, and it is a question no one has systematically answered before.

Section 2: The MinKav Project – A New Approach

On January 1, 2026, a team of German researchers began a three-year mission to change how propellers are designed. The MinKav project, funded by the state of Schleswig-Holstein with a €390,000 grant, is based at HAW Kiel and runs through December 2028 .

The team, led by Professor Jörn Kröger and doctoral researcher Leonie Föhring, brings together expertise in shipbuilding, maritime technology, and acoustics. They are partnered with JASCO-ShipConsult, a specialist firm with deep experience in ship acoustics .

Their methodology is rigorous. In the cavitation tunnel, they can recreate the precise conditions a propeller experiences at sea. High-speed cameras capture bubble dynamics that occur in milliseconds. Underwater microphones (hydrophones) measure the resulting sound. And sophisticated computer flow simulations allow them to test design variations before any metal is cut .

The goal is ambitious: to develop practical methods that allow noise reduction to be routinely integrated into propeller design, without the penalty of lost efficiency or speed. As Professor Kröger puts it, “We need practical methods that allow noise reduction to be routinely integrated into propeller design. We want to ensure these changes do not cause significant losses in efficiency or speed” .

This last point is critical. Current solutions often require ships to slow down to reduce cavitation. But slower ships mean longer voyages, higher fuel consumption, and increased costs—a non-starter for commercial operators. MinKav aims to break this trade-off.

Section 3: Why Now? The Regulatory and Environmental Pressure

The MinKav project did not emerge from a vacuum. It is a direct response to growing regulatory and environmental pressure.

In March 2024, the European Commission issued a notice under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive setting threshold values for underwater noise. For continuous low-frequency noise, the threshold for “biologically adverse effects” on marine species was set at 20% of habitat area . While this does not impose specific noise limits on individual ships, it requires EU member states to evaluate the health of their waters and take action if thresholds are exceeded .

This creates a powerful incentive for action. Ship owners and operators know that regulation is coming, and those who act early will have a competitive advantage.

Dr. Dietrich Wittekind, a shipbuilding engineer with JASCO-ShipConsult, sees a clear gap in current knowledge. Despite two decades of international research into low-frequency noise, he says, “we still lack a fundamental understanding of the mechanism responsible for the high noise levels, and therefore the basis for making ships quieter” .

“This is precisely where MinKav begins,” Wittekind adds. “It is the first project to systematically analyze the root causes and develop concrete solutions for significant noise reduction through propeller measures” .

Section 4: Parallel Innovations – Global Efforts in Quiet Propeller Design

While MinKav represents a significant step forward, it is not the only game in town. Engineers around the world are developing creative solutions to the cavitation problem.

Dimpled Tip Treatment

One of the most promising approaches comes from researchers studying tip vortex cavitation (TVC)—the cavitation that forms at the very tip of the propeller blade, which is often the first type to appear. In a paper published in Ocean Engineering in July 2025, a team led by Yang Li demonstrated that adding microscopic dimples to the blade tip can dramatically reduce cavitation .

The mechanism is subtle but effective. The dimples generate small induced vortices that interact with the main tip vortex, increasing flow instability and dispersing vorticity. This reduces the pressure gradient at the vortex core, suppressing cavitation while limiting propeller efficiency losses to within 3%. Under high-load conditions, the cavitation volume reduction reached an astonishing 81% .

PressurePores™ Technology

A different approach comes from Oscar Propulsion Limited and the University of Strathclyde. Their patented PressurePores™ system places a small number of strategically drilled holes in the propeller blades. These holes relieve pressure and reduce tip vortex cavitation .

After four years of CFD modeling and cavitation tunnel tests, the system demonstrated cavitation volume reductions of nearly 14% and noise reductions of up to 10dB. Importantly, the holes are not simply drilled at random. “We know exactly where to place the holes for maximum efficiency and for optimum noise reduction,” explains Lars Eikeland, Marine Director at Oscar Propulsion .

The technology can be applied to new propellers or retrofitted to existing vessels, making it particularly attractive for fleet-wide adoption.

The LOWNOISER Project

At the European level, the LOWNOISER project (LOWering underwater NOISE Radiation from waterborne transport) is taking a comprehensive approach. Funded under the EU Horizon program, LOWNOISER brings together 15 partners from across Europe to demonstrate noise reduction technologies at full scale .

The project combines existing and adaptable technologies, develops better prediction tools, and aims to create industry guidelines and certification frameworks. In June 2025, researchers at Finland’s VTT successfully simulated a lab-scale ship structure equipped with vibration dampers, targeting the low-frequency bands (63Hz and 125Hz) that are most harmful to marine life .

Section 5: The Engineering Challenge – Balancing Trade-Offs

Despite these advances, significant engineering challenges remain.

The first is the fidelity-speed trade-off. High-fidelity simulations of cavitation are computationally expensive. Running a full large eddy simulation (LES) on a single propeller design can take days or weeks, making it impractical for iterative design optimization. Researchers are developing reduced-order models and surrogate models to accelerate this process, but the perfect solution remains elusive .

The second challenge is retrofitting. The global fleet consists of tens of thousands of existing vessels. Any solution that only applies to new builds will take decades to have meaningful impact. Technologies like PressurePores™ that can be retrofitted are therefore particularly valuable .

The third challenge is integration. Propeller design is already a complex optimization problem involving thrust, efficiency, strength, and now noise. Adding a new constraint forces engineers to make trade-offs. The goal of MinKav and similar projects is to ensure those trade-offs are minimal.

As Leonie Föhring eloquently puts it, the aim is to “link species protection through noise reduction with climate protection through energy efficiency” . This is not just an environmental goal—it is an engineering one.

Section 6: What Success Looks Like – A Quieter Ocean by 2030?

The MinKav project will run through December 2028. By its conclusion, researchers hope to deliver a clear set of design guidelines that shipbuilders and propeller manufacturers can immediately apply .

If successful, the implications are profound. New vessels could be designed from the keel up with silent operation as a core requirement. Existing vessels could be retrofitted with optimized blades or tip treatments. And the cumulative effect on ocean noise could be dramatic.

This matters because noise pollution is cumulative. Every ship adds to the background din. Reducing the noise from each vessel, even by a few decibels, multiplies across the fleet.

There are also military implications. Quieter propellers make vessels harder to detect—a fact not lost on navies around the world. The same research that protects whales can also protect warships.

The Engineer as Ocean Steward

For generations, engineers designed propellers to be strong, efficient, and durable. Noise was not a consideration. It was simply not on the specification sheet.

That is changing. The engineers at HAW Kiel, the researchers publishing in Ocean Engineering, and the innovators at Oscar Propulsion are writing a new chapter in marine engineering. They are proving that it is possible to design for the environment without sacrificing performance.

The ocean will always be a noisy place. Waves crash, ice cracks, and marine animals call to one another across vast distances. But the deafening roar of cavitating propellers does not have to be part of that natural soundscape.

With continued research and engineering ingenuity, the ships of the future will move through the sea not as unwelcome intruders, but as quiet guests.

Sources Cited

- Interesting Engineering. (2026, February 19). “Engineers build quietest ship propellers to save marine life.” Retrieved from https://interestingengineering.com/innovation/ship-propellers-noise-reduction-efficiency

- Splash247. (2026, February 18). “Kiel project aims to quiet cavitating propellers without cutting efficiency.” Retrieved from https://splash247.com/kiel-project-aims-to-quiet-cavitating-propellers-without-cutting-efficiency/

- Marine Insight. (2026, February 19). “German Researchers Commence €390,000 Project To Reduce Cavitation Noise From Ships.” Retrieved from https://www.marineinsight.com/shipping-news/german-researchers-commence-e390000-project-to-reduce-cavitation-noise-from-ships/

- CORDIS | European Commission. (2025). “LOWering underwater NOISE Radiation from waterborne transport (LOWNOISER) Project.” Retrieved from https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101192302

- Li, Y., Zhao, D., Deng, F., & Zhang, L. (2025). “Propeller tip vortex cavitation suppression by dimpled tip treatment.” Ocean Engineering, 331, 121297. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0029801825010108

- Hydro International. (2025, July 2). “Innovative research moves shipping closer to quieter ocean.” Retrieved from https://www.hydro-international.com/content/news/innovative-research-moves-shipping-closer-to-quieter-ocean

- World Ports Organization. (2024, July 5). “Pressure On To Reduce Underwater Radiated Noise From The Ship’s Propeller.” Retrieved from https://www.worldports.org/pressure-on-to-reduce-underwater-radiated-noise-from-the-ships-propeller/

- Lü, S. J., Han, C. Z., Yang, R., et al. (2025). “Numerical investigation of PPTC propeller cavitation noise characteristics and sound generation mechanism.” Chinese Journal of Ship Research, 20(4), 57–69. Retrieved from https://www.ship-research.com/en/article/doi/10.19693/j.issn.1673-3185.04119