Engineers from the University of Glasgow and Oles Honchar Dnipro National University in Ukraine recently built an autophage engine designed for launching satellites into space. Unlike standard models, this “self-eating” rocket engine could make the process of sending satellites into orbit easier and more affordably than ever before.

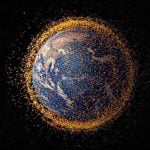

Rockets typically use tanks, often much heavier than the useful payload, to store their propellant as they climb. In addition to being extremely inefficient, this method also contributes heavily to the problem of space debris. An autophage engine, however, would cause the launch vehicle to consume its own structure during ascent, freeing up more space for cargo and reducing the amount of debris.

The engine consumes a propellant rod, which consists of solid fuel on the outside and oxidizer on the inside. By driving the rod into a hot engine, the fuel and oxidizer are vaporized into gases, which flow into the combustion chamber to produce thrust along with the heat required to vaporize the next section of propellant.

Varying the speed at which the rod is driven into the engine allowed it to be throttled, a capability that is quite rare in a solid motor. A series of tests involved firing up the engine and throttling it up and down, and rocket operations have thus far been sustained for 60 seconds at a time.

“Over the last decade, Glasgow has become a center of excellence for the UK space industry, particularly in small satellites known as CubeSats, which provide researchers with affordable access to space-based experiments,” said Dr. Patrick Harkness, Senior Lecturer at the University of Glasgow’s School of Engineering and Glasgow’s lead contributor. “There’s also potential for the UK’s planned spaceport to be based in Scotland.”

“However,” he continued, “launch vehicles tend to be large because you need a large amount of propellant to reach space. If you try to scale down, the volume of propellant falls more quickly than the mass of the structure, so there is a limit to how small you can go. You will be left with a vehicle that is smaller but, proportionately, too heavy to reach an orbital speed.”

The team set out to change that with the development of a rocket powered by an autophage engine. The propellant rod makes up the body of the rocket, and the engine works its way up, consuming the body from base to tip as the vehicle climbs. According to Harkness, the rocket structure would be consumed as fuel, thereby eliminating the problem of excessive structural mass.

“We could size the launch vehicles to match our small satellites and offer more rapid and more targeted access to space,” he said. “While we’re still at an early stage of development, we have an effective engine testbed in the laboratory in Dnipro, and we are working with our colleagues there to improve it still further.”

The engineers published a paper titled “Autophage Engines: Toward a Throttleable Solid Motor” in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. Going forward, the engineers will need to secure further funding, which will allow them to investigate how the engine might be incorporated into a launch vehicle.