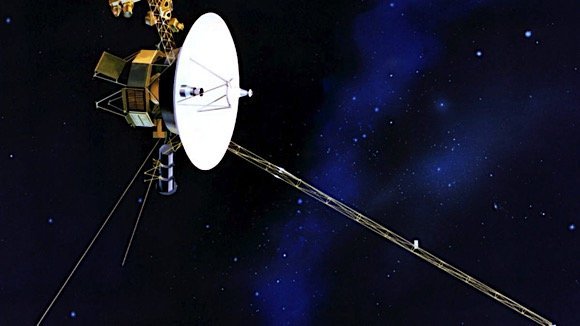

Twin spacecrafts Voyager 1 and 2 launched in 1977, 16 days apart. The Voyager missions were the first to discover active volcanoes beyond Earth, which were found on Jupiter’s moon, Io. They also discovered hints of a subsurface ocean on Jupiter’s moon, Europa.

To accurately fly past Voyager’s instruments, engineers used trajectory correction maneuver (TCM) thrusters. They are identical in size and functionality to the attitude control thrusters and are located on the back of the spacecraft. However, as Voyager’s last planetary encounter was Saturn on November 8, 1980, the TCM thrusters no longer needed to be used, so they remained stagnant.

Voyager 1 is the only manmade spacecraft travelling through interstellar space, after exiting our solar system in September 2013. It is currently 13 billion miles away from the earth and approximately two billion miles ahead of Voyager 2. Both spacecrafts continue to explore and communicate with Earth daily.

In 2014, mission managers noticed that some of the thrusters were not working as well as they had hoped. The team assembled a group of propulsion experts at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to study the problem. The group analyzed options and predicted how Voyager might respond in different scenarios, and they developed a plan for switching from the attitude control thrusters to the trajectory correction maneuver thrusters.

On November 28th, NASA ground controllers sent commands to the Voyager spacecraft to fire the backup thrusters, which had been idle for nearly four decades. Engineers conducted tests to gauge the thrusters’ ability to orient the spacecraft using 10-millisecond pulses. The spacecraft responded, and the thrusters fired as intended. NASA received the news 19 hours and 35 minutes after initiating the command.

The success of the testing was even more remarkable given the age of the equipment, the limited use, and the lack of experience using them in the manner that was needed for testing. Even when in use, they were fired continuously rather than in brief bursts necessary to orient the spacecraft.

The switch to the alternate thrusters from a set that is currently degrading will take place next month, potentially extending the spacecraft’s life by two to three years. Increasing its life span is important for mission controllers working with Voyager because it allows them to continue receiving more information. Voyager is in uncharted territory, so any information it can send back is new and groundbreaking, and it is extremely helpful in understanding more about what is out there in space.

“The Voyager flight team dug up decades-old data and examined the software that was coded in an outdated assembler language, to make sure we could safely test the thrusters,” said JPL Chief Engineer Chris Jones.

According the propulsion engineer Todd Barber, “The Voyager team got more excited each time with each milestone in the thruster test. The mood was one of relief, joy and incredulity after witnessing these well-rested thrusters pick up the baton as if no time had passed at all.”

The positive response has inspired NASA to attempt the test on Voyager 2 as well. That will be a while, however, as the current thrusters are functioning properly.

The Voyager will need to turn on one heater per thruster, which requires power. Unfortunately, power is a limited resource out there. When it has exhausted its power supply, the team will need to switch back to the attitude control thrusters.

Sources: