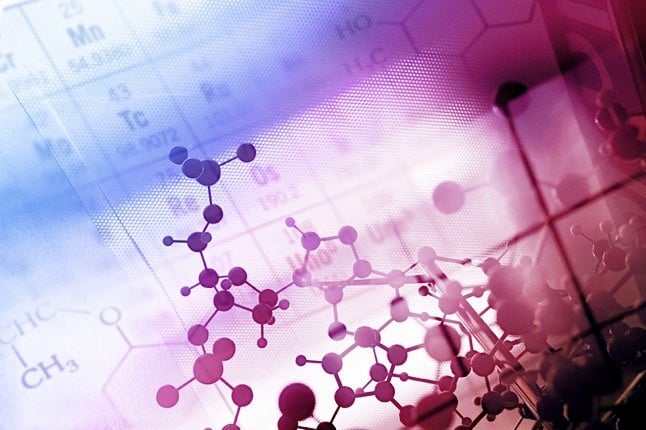

Researchers from the University of Portsmouth and the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory developed an enzyme by sheer accident while examining the structure of a natural enzyme found in a waste recycling center in Japan.

The enzyme, Ideonella Sakaiensis 201-F6, degrades polyethylene terephthalate, a substance that was patented as a plastic in the 1940s and is currently used to produce plastic bottles. This is an exciting and promising discovery, as plastic is currently expected to be as common in oceans as fish by the year 2050. Discoveries like this could curb that and greatly reduce the amount of garbage in oceans and landfills around the world.

The original aim of the study was to research the structure of the enzyme that had been found in Japan. “We hoped to determine its structure to aid in protein engineering, but we ended up going a step further and accidentally engineered an enzyme with improved performance at breaking down these plastics,” said lead researcher Gregg Beckham.

According to the University of Portsmouth, this remarkable enzyme “could result in a recycling solution for millions of tonnes of plastic bottles, made of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, which currently persists for hundreds of years in the environment.”

“Few could have predicted that since plastics became popular in the 1960s, huge plastic waste patches would be found floating in oceans or washed up on once pristine beaches all over the world,” said Portsmouth’s Instituted of Biological and Biomedical Sciences Director John McGeehan. “We can all play a significant part in dealing with the plastic problem, but the scientific community who ultimately created these ‘wonder-materials,’ must now use all the technology at their disposal to develop real solutions.”

Lead author Harris Austin, jointly funded by the University of Portsmouth and National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) stated that this was “just the beginning” for research on this enzyme and its potential. “I am delighted to be part of an international team that is tackling one of the biggest problems facing our planet.”

The enzyme is capable of breaking down plastics in only two days. However, it currently does not work on a larger scale. Going forward, Harris and his team of researchers hope to change that and are working to improve the enzyme, with the goal of allowing it to be used industrially to break down large amounts of plastic in a fraction of the time.