Researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison recently revealed new effects in tiny electronic devices known as quantum dots. The potential for this research is huge, as it could very well pave the way for highly advanced computer systems. The findings of this research were recently published in the journal Nano Letters.

The researchers developed and applied analysis methods that they hope will aid in the development of electronic materials. “We can now look at a set of structures that people couldn’t look at before,” said University of Wisconsin-Madison Professor of Materials Science and Engineering Paul Evans. “In these structures, there are new sets of crucial materials problems that we previously weren’t able to think about solving.”

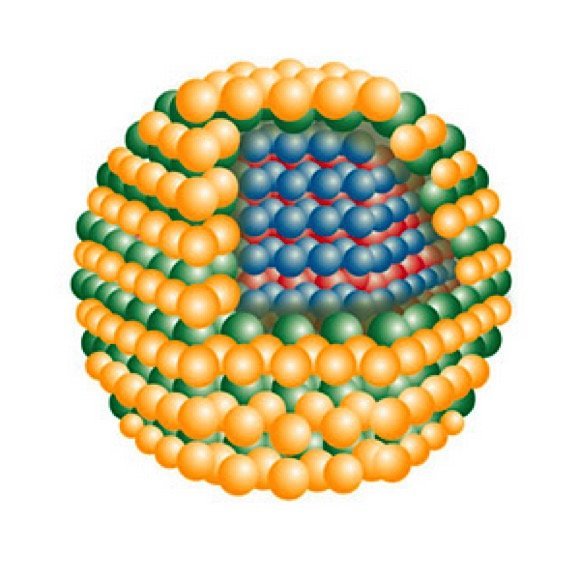

The structures are thousands of times more narrow than single sheets of paper and much smaller than the dimensions of individual human cells. Quantum dots within the structures form inside very thin stacks of crystalline materials topped by an asymmetrical arrangement of flat, metallic electrodes. Quantum dots are located between those metallic electrodes.

Creating these intricate structures and looking inside them and into the tiny spaces is challenging enough as it is, and it is even more difficult as quantum dots do not always behave as expected. Evans worked with a team of collaborators at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. These collaborators had previously created and studied the crystal stack structures, which led to suspicions that the quantum dots were different in important ways from what had been designed. Until recently, measuring those differences was an impossible task.

“Previous imaging approaches and the modeling weren’t allowing people to structurally characterize quantum dot devices at this tiny scale,” said Anastasios Pateras, a postdoctoral scholar who authored the paper.

The researchers pioneered a strategy for using beams of very tightly focused X-rays to characterize the quantum dot devices, which allowed them to observe shifts in the spacing and orientation of atomic layers within the quantum dots. “Quantum dots need to be close to perfect,” said Evans. “This small deviation from perfection is important.”

The discovery indicates that the process of creating quantum dots distorts the material underneath, creating strain in the material and leading to small distortions in the dots themselves. Understanding this effect and effectively exploiting that fact could aid researchers in the improvement of quantum dot behavior. “Once you know these quantities,” said Evans, “then you can design devices that take into account that structure.”

“This is going to be very relevant because, right now, there are multiple sources of decoherence quantum dots,” said Pateras.

Going forward, the researchers are developing an algorithm to automatically visualize atomic positions in crystals from X-ray scattering patterns. They are also exploring how the techniques could provide insight into other structures that are difficult to study.