The ideal indoor lighting would replicate the natural light of the sun. That light is made up of all the visible colours of the spectrum, as well as a couple that are invisible (ultraviolet and infrared), to humans. So far, the goal of creating LED light bulbs that can accomplish this feat has been less than completely successful. The reason can be found in the way that LED lights work.

The light given off by an LED (light-emitting diode) is caused by electrons passing through a semiconductor and contacting phosphors that glow and emit a specific colour when excited by the electrons. It is easy, says a team at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), a research lab supported by the US Department of Energy, to create LEDs that produce a single colour—red, or green, say. But to create light that approximates sunlight would require phosphors that were capable of glowing in all the different colours that make up “white” light.

A scientist at ORNL, John Budai, said in a release that they might have come up with a way to do it. It involves hitting a mixture of phosphors with ultraviolet radiation from an LED. This, he says, stimulates the many colours needed for white light.

Budai and his team are working with specially grown nanocrystals made from aluminum oxide and the rare earth element europium. Europium oxide has good phosphorescent properties. The new crystals, two of which had never been seen before, “might” yield the right blend of colours for LEDs that give truly warm white light, like the sun’s.

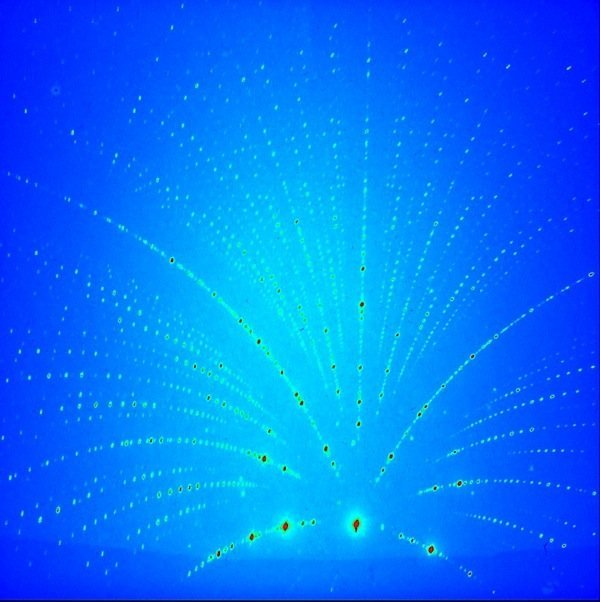

“What’s amazing about these compounds is that they glow in lots of different colours—some are orange, purple, green or yellow,” Budai said. “The next question became: why are they different colours? It turns out that the atomic structures are very different.”

The scientists are using X-ray diffraction analysis to work out how the atoms are arranged in each of the different crystal types. The different-colored phosphors exhibit distinct diffraction patterns when they are hit with x-rays, enabling researchers to analyze the crystal structure.

Once the researchers understand how to modify the composition of the phosphorescent crystals, they hope they’ll be able to perfect the “recipe” and improve the crystals’ ability to produce the white light they want. It may turn out that the materials’ luminescence has other applications, such as in fiber optics.

“You can keep growing the crystals and measuring them, or you can understand why it’s doing what it’s doing, and figure out how to make it better. That’s what we’re doing—basic research. We have to figure out nature first.”

Reprinted with permission of the G4 Report.